This article was originally published on LiveLaw on 24 July 2020, and can be viewed here.

This article was originally published on LiveLaw on 24 July 2020, and can be viewed here.

As multitudes of migrant workers took to the streets to walk hundreds of kilometres away from India’s cities, even as the COVID-lockdown had compelled everyone else to stay in their homes, it inevitably brought to fore the scale of the housing crises[1] [2] which plagues some of the major cities and towns in India. In response, the government announced a slew of measures including the affordable rental housing scheme[3], while a few state governments turned their attention to land reforms[4] [5], specifically in the agriculture sector. With the pandemic-induced lockdown having emboldened the fault lines of socio-economic inequality in our country, the conversation about the need for secure property rights to address the vulnerabilities of slum dwellers, migrant labourers, marginalized women and young girls, tribal communities among others, became all the more urgent.

When we talk about property rights, we don’t just talk about the right to own a piece of land or live in a house. The conversation about property rights is instead a complex mesh of narratives weaved around socio-economic, geographic, legal and cultural lines, all of which play a critical role in determining who has the access to land and to what extent.

The benefits of secure property rights are, therefore, manifold. Owning a house or a piece of land not just offers physical security, but the proof of address further makes the owner visible in government records and makes them eligible to open a bank account, send their children to school, access financial credit and other welfare benefits. Over the years, several studies have also shown that a secure land tenure leads to better educational and health outcomes for the household. According to an RBI report, over 70% of an Indian household’s assets are held in land and housing[6], yet households struggle to leverage this asset and gain maximum economic benefit. An oft heard complaint is the lack of clear land titles in India, and there is a growing clamour for “conclusive” land titles. Yet it is important to understand that the basic foundations of the land administration need to be strong before “conclusive” land titles can be established. The myriad issues cut across socio-economic dynamics within communities, weak land administration and governance frameworks, and judicial bottlenecks among other factors. However, this is an important journey the country needs to undertake, and there is no better time to start than now.

Navigating the (lack of) data

What gets measured, gets done. Yet the first element that strikes anyone looking to better understand the state of land and property rights in India is the lack of reliable and consistent data. This becomes especially critical when we look at vulnerable groups, such as women and minority communities. There are very few national level surveys that captures gender-disaggregated information on land and property rights, which includes the Agriculture Census (which says that 14% of agricultural land holders are women, operating 12% of total agricultural land), and the National Family Health Survey (NHFS). However, while these surveys measure gender-disaggregated property ownership data, it has several gaps, such as it does not provide insights into ownership among older family members or percentage of female landowners to all landowners, etc. [7]

Women and land

Figure 1 – Chart showing data on women’s property ownershipGiven that land laws are a state subject, there is significant variation in the nature of rights guaranteed to women. In certain north-western states, the succession laws explicitly prefer male descendants over females, and grants restricted land rights to women, wherein they lose their claim to the property when she remarries.

In several states including Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh, till date, the law has explicit provisions deterring women from inheriting agricultural land[8], and their names are not included in land records. Owing to this and other patriarchal biases in traditional practices, a large population of women have been excluded from owning agricultural land.

Landless labourers

Figure 2 – Map showing incidence of tenancyThe Agricultural Census of 2015 estimates that even though 73.2% of rural women workers are engaged in agriculture, they own only 12.8% of all land holdings[9]. According to the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census, the incidence of landlessness is the highest among Dalits or scheduled caste, which suggests that around 45 per cent of SCs are both landless and derive a major part of income from manual casual labour. The 2011 Census also records that nearly 70% of Dalit farmers work as labourers on farms owned by other[10]. These landless agricultural labourers remain invisible in the government welfare records and are unable to gain from the benefits and concessions provided by the government to land-owning farmers. The situation for landless labourers is further worsened by the lack of recognition for tenant farmers as per the legal framework in most states, owing to which we have very poor visibility on the extent of agricultural tenancy in the country. The National Sample Survey Office estimates that at least 13% of all farmers lease in land[11], but the actual figures could be much higher due to informal tenancy arrangements (refer figure 2).

Scheduled Tribes and Forest Rights

Figure 3 – Property ownership among marginalized communitiesLand ownership is also poor among Adivasis, with reports stating that millions of Adivasis across India are still awaiting access to land rights which they are entitled to under the Forest Rights Act, 2006[12]. The monthly progress report for June 2020 made available by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs state that a total of 4.2 million claims filed, only 1.9 million individual forest rights titles and over 76,000 community titles have been distributed. As per the data made available by NSSO, the proportion of Adivasi households that did not own any land went up from 16 percent in 1987-88 to 24 percent in 2011-12[13].

Judicial and social burden of land conflicts

In the Indian courts, land disputes occupy the largest set of cases. One of our every four cases heard by the Supreme Court involves conflict over land, whereas nearly 2 out of every 3 civil case is related to land or property dispute. Land disputes are also often the most commonly cited motive for other forms of crimes, including murder. According to the National Crime Records Bureau’s 2017 report, in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar (states with the most murder cases), of all recorded cases of murder, 7.2% and 33.5% of cases respectively were due to land and property related disputes.

The rampant incidences of land disputes have been contributed by conflicting laws and inadequate policies (a study by Centre for Policy Research has mapped over 1000 land laws in the country, some of which are conflicting[14]) as well as poor administrative practices, and other social factors.

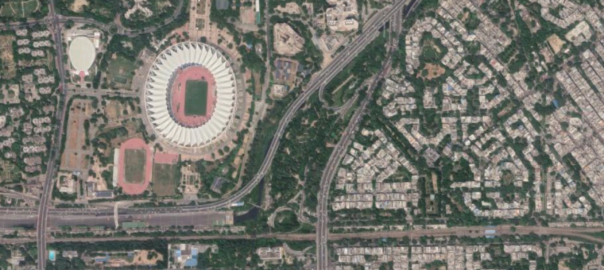

Affordable housing in urban India

Panning the lens to urban India, the nature of problems when it comes to property rights varies significantly, with affordable housing being one of the key issues. According to the 2011 Census, nearly 35 million households (out of the 192 million surveyed households) reportedly live in temporary housing[15]. Rapid urbanization and the lack of supply in providing affordable housing has resulted in the expansion of slums in Indian cities, with nearly 33-47% of the urban population living in informal housing, which includes slums and other unauthorised settlements[16]. The expansion of slums not only affects urban planning, but it adds to the woes of the slum dwellers who live in fear of forced eviction and have poor access to basic services such as sanitation, water, electricity, secure and safe housing among others, with their vulnerability magnified during public health crises and other disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore, slum dwellers also experience poor social upward mobility, as a lack of proper identification and address leaves them out of the government welfare databases and restricts their ability to seek bank loans or credits. Even the government’s flagship affordable housing programme, the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana requires the beneficiaries to have land ownership to be able to access benefits and upgrade their house. Slums are also automatically ruled out of this scheme, as it only recognizes owners of houses which are larger than 21sqm as the target beneficiaries. Secure property rights for slum dwellers are not just essential for better social indicators for the community at large, but it is also a valuable source of revenue for the administrative authorities. It is estimated that updated databases of slums and informal settlements can lead to increase in municipal property tax revenues as they have significant property transactions, which is otherwise lost revenue for the city and grounds for increased risk to its residents.

Land Rights for a Billion

The issues that deter the access to property rights are myriad and complex in any country, let alone in one as socio-culturally and politically diverse as India. However, even as the scale of the challenges may seem daunting, there’s also much to pin our hopes on in this conversation to secure land rights for a billion, and certain conversations around property rights in the country has emerged as the silver lining even under the dark cloud of the pandemic this year. For instance, the dialogue around land reforms was refuelled, the call for strengthening the affordable rental housing market reinforced, and the country also saw some innovative schemes such as the SVAMITVA scheme which aims to provide record of property ownership to inhabitants of abadi areas. The Indian government also announced its intention to role out a Model Tenancy Act, which is posited to reduce tenant-landlord conflicts in the leasing and renting of residential properties. Furthermore, in an encouraging development for women’s property rights, the Supreme Court also upheld the Hindu Succession Amendment Act, 2005, granting coparcenary rights to daughters.

Knowing who have been denied access to property rights and the consequences of such a denial is an important step towards achieving healthier socio-economic indicators. With land being a finite asset, better governance and administration of property rights is required to ensure secure property rights for all. However, to find solutions to the numerous challenges which have been crippling secure property rights in our country, there’s a need for a collaborative ecosystem of funders, researchers and policymakers among others to come together and drive interdisciplinary research and produce evidence-based solutions which is attuned to India’s socio-economic realities.

(Sneha Pillai is the Communications and Advocacy Lead at The Quantum Hub Consulting, a Delhi-based policy and communications consulting firm.)

[1] Jain, V., Chennuri, S., & Karamchandani, A. (2016). Informal Housing, Inadequate Property Rights. Mumbai: FSG. Retrieved from https://citiesalliance.org/sites/default/files/Informal%20Housing,%20Inadequate%20Property%20Rights.pdf

[2] 2011 Census data. Retrieved from https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/hlo/Data_sheet/J&K/Figures_glance.pdf

[3] https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/cabinet-approves-rental-housing-scheme-for-migrants-govt-to-spend-rs-600-crore/story-Waf7MhRD7Lq8t74oNmcC6J.html

[4] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/karnataka-assembly-passes-amendment-to-land-reforms-act-makes-it-easy-to-buy-farm-land/articleshow/78336440.cms

[5] https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/100920/telangana-cm-introduces-landmark-land-reforms-legislation-in-assembly.html

[6] Report of the Household Finance Committee, Reserve Bank of India, July 2017. Retrieved from: https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/HFCRA28D0415E2144A009112DD314ECF5C07.PDF

[7] Agarwal, B., Anthwal, R. and Malvika, M. (2020). Which women own land in India?

Between divergent data sets, measures and laws. GDI Working Paper 2020-043.

Manchester: The University of Manchester

[8] https://www.indialegallive.com/cover-story-articles/il-feature-news/no-womens-land/

[9] Agricultural Census 2015. Retrieved from http://krishi.maharashtra.gov.in/Site/Upload/Pdf/Agriculture%20Census%202015-2016%20Final%20for%20website_part3_pages36-60.pdf

[10] 2011 Census data. Retrieved from https://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/B-series/B_7.html

[11] https://www.indiaspend.com/land-reforms-have-failed-formalising-tenancy-only-option-to-address-farm-distress-62357/

[12] https://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/forests/how-government-is-subverting-forest-rights-act-2187

[13] http://ras.org.in/scheduled_tribe_households

[14] https://www.cnbctv18.com/legal/hundreds-of-indian-land-laws-cause-confusion-conflict-researchers-2640041.htm

[15] 2011 Census data. Retrieved from https://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/housing.aspx

[16] Jain, V., Chennuri, S., & Karamchandani, A. (2016). Informal Housing, Inadequate Property Rights. Mumbai: FSG. Retrieved from https://citiesalliance.org/sites/default/files/Informal%20Housing,%20Inadequate%20Property%20Rights.pdf

This article was originally published on

This article was originally published on